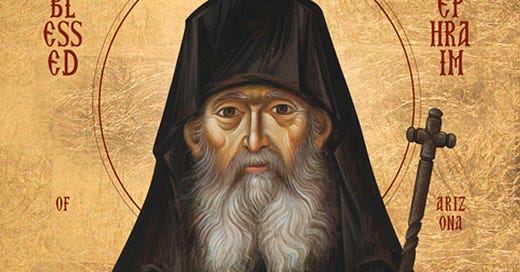

Yesterday, I drove from my home in Maricopa, Arizona, to St. Anthony the Great’s Monastery in Florence, Arizona. This monastery was founded by Blessed Ephraim of Arizona. He was an Athonite monk who came to the United States and established a great number of monastic communities. St. Anthony’s is particularly notable because it is where the great saint lived, died, and is entombed. He is already venerated locally but will likely be canonized soon.

Upon visiting the monastery, I was warmly greeted by some women who were running the bookstore near the entrance. They were very kind in showing me a map of the grounds and describing the various architectural nuances in the buildings (Russian, Greek, Romanian, etc.). After orienting myself, I began my journey throughout the property. It was beautiful beyond compare and provided the perfect place for prayer and meditation.

I won’t detail my entire journey through the monastery grounds, as that would take far too long, but I will mention my first stop and the highlight of my visit. It was a chapel that (I am told) was built in Greece, transported to the USA, and reassembled at the monastery. Inside it, Blessed Ephraim of Arizona is entombed. By the grace of God, I was able to go inside and venerate his tomb. It was a very holy and personal moment. I will cherish it as long as I live.

The chapel itself was beautiful, with two massive icons on the outside and carved wooden doors at the entrance. It was certainly the most beautiful building on the property.

As I continued walking throughout the grounds, I felt a growing sense of peace, wholeness, and home—like one who has returned to a place of prior dwelling, overwhelmed with nostalgia.

This leads me to the point of this post: As Anglicans, we have a very close relationship with Holy Orthodoxy. Prior to the Great Schism, we were undoubtedly Western Orthodox. Our spirituality was distinctly Anglican, but we were certain members of the undivided Church. After the Great Schism, we remained this way. We continued to preserve our Western and Celtic heritage without the baggage of Papal identity until the Norman Conquest. After this, we were essentially brought by force into the Papal Church.

All this to say, as a deeply convicted Anglican, I believe that our future is Orthodox because I believe that is who we are. During the Reformation, our rejection of Papal Supremacy was Orthodox. The recovery of our spirituality, codified in the Book of Common Prayer, is Orthodox. This is even affirmed by the canonical Orthodox Church, which, under Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow, adopted our Anglican liturgy as Orthodox. To this day, Western Rite Orthodox parishes can be found worshiping using the Mass of St. Tikhon, which is the American 1928 Book of Common Prayer Mass with some minor changes. The importance of this cannot be understated. Anglicans are Orthodox as acknowledged by Orthodoxy!

Thus, looking into the future—as uncertain as it is—I have hope for an Anglican Orthodoxy to emerge. Communion with the historic patriarchates, while not essential for sacramental unity with the Church, is important for the visible demonstration of unity that Christ prays for. It is my hope, as one who deeply loves the Orthodox Church, that they would more deeply acknowledge the Orthodoxy of Anglicanism and allow us into the fold without requiring us to abandon our unique cultural heritage, which, at its best, is thoroughly Orthodox.

For Anglicans committed to their historic faith, we are simply Western Orthodox Christians, bound to the dogma of Holy Scripture, the Creeds, and the Seven Ecumenical Councils. Sure, we have a tumultuous history that contains certain things we must be willing to cut ties with, but what tradition doesn’t have these skeletons? In the end, our Orthodoxy stands firm.

As I walked the grounds of St. Anthony’s, a deeply Athonite and Greek monastery, I felt at home. Their faith is my faith. Though our expression bears the reality of our culture, the substance of the confession is the same. I rejoice in this and pray for the day—hopefully soon—when all sides recognize this reality and can come to feast at the same altar.

I would like this to be so, and think that it has been and still could be. There are, however, certain areas of contention. It is hard to see the English church, evinced by St Bede, as other than "Roman" since the Augustine mission of 596 and all the more so since Whitby (664), though your point still stands, since Rome was as yet in communion with the other great patriarchates - the appointment of a Greek bishop, St Theodore of Tarsus, as Archbishop of Canterbury in 669 attests to this. That the Reformation was in part a reaction to over-Romanisation of the Western Church is surely also true, and buttressed by the Reformers' constant appeal not only to Scripture, but to the Fathers of West and East. Their sacramental theology also owed something to the East. The degradation of the cult of the saints, veneration of relics and ban on veneration of images, however, was far from Orthodoxy, and I am glad that in most Anglican provinces those errors have now been rectified. We have, alas, fallen into other ones, ranging from outright Calvinism to unilateral decisions on church order which run contrary to Scripture, tradition and the universal consensus of the Church. These preclude reunion. However, in those Anglican churches which have resisted or revised such errors, there is indeed hope for unity with the East, and for certain parts of the Anglican world to be the Western Orthodoxy that we truly should be. Ut unum simus!

I had a brief stop-over in high church Anglicanism before becoming Orthodox, and can credit a specific Anglo-Catholic parish as my first exposure to truly transcendent liturgy, which I am very grateful for. In fact we can probably in large part blame the absence of any high church Anglican parishes in my area for my eventual crossing of the Bosporus. All that to say I am still very interested in what high church Anglicans think and mean the following as sincere inquiry, and not polemics.

My question is, how reunion would work on the ground level regarding sacraments and liturgical practice (I'll leave ecclesiology to people who actually know what they're talking about)? From our point of view, reunion would at minimum require acknowledgment by all we come into communion with that there are (at least) seven Sacraments, of veneration of relics, icons, and the saints not as just an option but as necessary, that after the Consecration there is not only the Real Presence of Christ but also an absence of any more bread or wine, of paedocommunion, and probably plenty more I'm forgetting.

I'm sure many or most Anglo-Catholics could follow on those points, but I'm not sure about the balance of Anglicanism. I can recall from my time in Anglicanism that it was sometimes hard enough to agree with my fellow parishioners that Christ was truly present after the Consecration, much less that only Christ was present on the altar. I myself moved in high church circles without accepting the intercession of saints or veneration of icons and relics - those were practices I only came to understand and accept during my conversion to Orthodoxy.

I completely agree regarding Western Orthodoxy in the British Isles up to the Norman Conquest, and of course agree that reunification is desirable (and for what it's worth, my personal opinion is that Anglicanism is the best prospect for that after the Oriental Orthodox). My hesitation is that it seems much of the optimism regarding union from the 19th Century to today, both on the part of Anglo-Catholics and the Orthodox, stems in part from ignoring the broad swaths of more Reformed Anglicanism.

Apologies for the long comment, and a blessed remainder of Lent to you and your parish.